It’s recently been announced that the government is going to consider plans to build specialist units inside prisons to treat prisoners with mental health problems. Currently, the most dangerous offenders are sent to Ashworth, Broadmoor or Rampton for treatment, but some receive little or no help. The question of how to treat mentally ill offenders pre-dates the construction of Broadmoor (1863), Britain’s first hospital for mentally ill criminals, and has always been highly contentious. This posts outlines the contention that existed at Victorian Broadmoor regarding the committal of insane convicts into the asylum. There were two types of patient at Victorian Broadmoor: Queen’s pleasure patients (individuals found insane when tried) and insane convicts (those convicted of a crime and transferred to Broadmoor from prison after allegedly developing insanity whilst incarcerated).

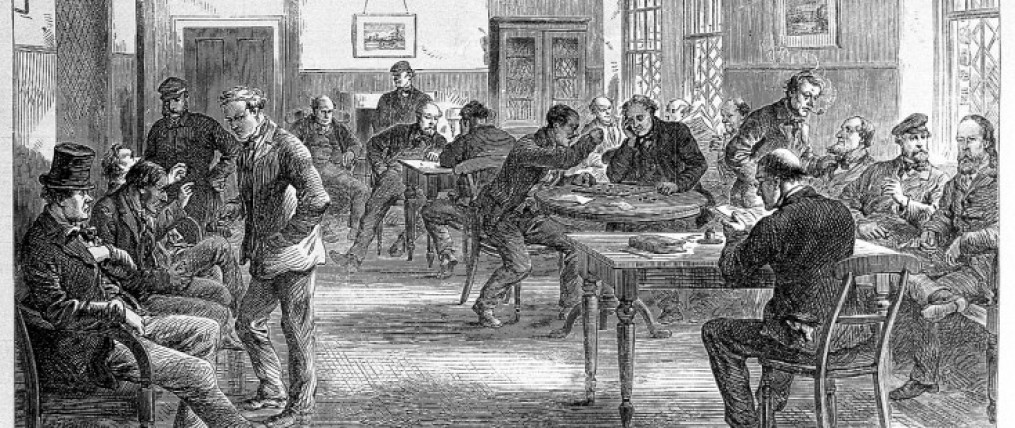

There had long been discussions in Parliament and between Lunacy Commissioners and Broadmoor’s Superintendents about whether convicts should be incarcerated at Broadmoor and the extent to which they should be allowed to associate with Queen’s pleasure patients. In May 1860, three years before Broadmoor opened, the Lunacy Commissioners reported the result of their examination of the draft Criminal Lunatics Act to the Home Secretary. Perhaps basing their conclusions on the reservations of MPs, journalists, asylum Superintendents and prison governors, all of whom objected to the association of criminals and the insane, they stated that the reception of convicts into Broadmoor ‘would be most objectionable, and […] the proper place for the[m] […] would be an institution […] in connection with convict prisons.’ Yet, not long after Broadmoor opened, the Lunacy Commissioners declared, ‘it is the matter of the gravest doubt whether insane persons of the criminal class […] should be treated differently from other patients.’ But the behaviour and presumed natural propensities of convicts (that they were inherently lazy and bad) meant they were considered radically different to Queen’s pleasure patients, and when William Orange became Medical Superintendent in 1870 he initiated great change: he separated Queen’s pleasure patients and insane convicts because he believed that ‘unrestricted association leads to the […] further deterioration, morally, of the patients.’ After years of observing the violent and abusive nature of insane convicts in Broadmoor and hearing damning testimonies from the Superintendents and Queen’s pleasure patients regarding their behaviour, the Lunacy Commissioners agreed.

Although he viewed criminals and the insane in a similar light, Italian criminologist, Cesare Lombroso, admired Orange’s efforts to separate the classes. He reported that there had been a reduced number of attacks made against attendants and that the conditions at Broadmoor had ‘greatly improved’ since the disassociation of the two classes. This observation was partly true but evidence suggests that the separation of classes was insufficient and Broadmoor’s resources were, as Orange reflected, ‘strained beyond the limits of prudence’ in the attempt to treat both classes of patient and change was needed. The Lunacy Commissioners were in agreement:

The forced association of honest and well-conducted persons who, solely owing to mental disease have broken the law, with convicts whose criminal acts have probably been the cause of their mental disorder is evidently unjust, and there is every reason to believe that the successful management and treatment of both classes should be more safely and efficiently conducted in separate institutions, with different rules and modes of treatment, and wherein the structural arrangements can be specially adapted to the varying requirement of each.

In 1874 it was decided that insane convicts should be incarcerated at Woking Prison instead of Broadmoor. This meant that through death, transfer or discharge, the numbers of convicts in the asylum gradually declined.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that Broadmoor’s stance towards convicts appears to have been changing at the same time damning images of the criminal were emerging in scientific and legal discourse. An examination of the Addresses, publications and Annual Reports of Broadmoor’s Superintendents – William Orange and David Nicolson (Superintendent 1886-1896) suggests that they shared many of the same views as men such as Edmund Du Cane (chairman of the prison commission) and psychiatrist Henry Maudsley who tended to represent (habitual) criminals (as most of Broadmoor’s convict population were presumed to be) as amoral, uncivilized and untreatable: they were not industrious, they failed to control their passions and they were physically weak and deformed.

The positive effects on asylum life as a result of the prohibition of convicts were soon realised – there was ‘less bad language […] [and] fewer attacks by patients on each other take place, as shown by the comparative absence of bruises, and in all respects [patients] have become more manageable.’ It was not to last, however. Home Office records indicate that contention existed regarding the committal of insane convicts at Woking. Some, including the Lunacy Commissioners, questioned the legality of housing insane convicts in a prison rather than a legally recognised criminal lunatic asylum. Others believed Woking was unsuitable to house insane convicts and one contemporary reported to the Home Office: ‘no alterations can make Woking prison as good or convenient place for the treatment and detention of the insane as Broadmoor.’ In 1886 it was decided to discontinue the occupation of Woking by insane convicts and the following year work began at Broadmoor to construct a Block specifically for convicts in preparation for their re-admission into the asylum. In October 1888 the transfer of convicts back to Broadmoor began. The asylum reportedly soon witnessed an increase in the ‘proportion of restless, turbulent, and viciously disposed inmates.’

Where (and even if) mentally ill offenders should be treated in the nineteenth century was certainly the cause of much debate – it was proposed in the British Medical Journal that insane convicts should be kept in a separate institution where they could receive specialised treatment, and the Pall Mall Gazette refused to the pity the repeat offender (the ‘hardened criminal’) who became insane, advising that it was probably better to hang than treat them. Recent press coverage regarding debates over the provision of books for prisoners (‘Books […] [are] a way of nourishing the mind’)[i], and discussions of how and where mentally ill prisoners should be treated, indicate that the question of how best to treat them remains to this day – albeit, thankfully, in more sympathetic terms.

[i] Victorian psychiatrists expressed similar beliefs. Broadmoor’s Superintendents and Chaplain wrote about the positive effect reading had on patients’ minds. Broadmoor’s Council of Supervision (its governing body) purchased books for the patients which Reverend Burt described as being ‘of great moral value; they afford mental occupation to a considerable number of all classes of patients, and both amuse and instruct them during many hours which, without this humane provision, would be spent in weariness, in bitter reflection, or in angry discontent.’

Nice Blog, thanks for sharing this kind of information.